Fairmont Gold Pieces, Part VI: The No Motto $5s - Time Series Analysis

/a guest blog by Richard Radick

Introduction: The Fairmont No Motto Half Eagles

As of late 2024, the Fairmont Collection comprises more than 8,000 US gold coins, graded by the Professional Coin Grading Service (PCGS) and bearing “The Fairmont Collection” pedigree on their holders. These coins have been marketed by Stack’s Bowers Galleries (SBG) in a series of auctions that began in June, 2018. It is now evident that the Fairmont Collection, as defined above, is only a small part of a much larger parent population of more than 400,000 coins, encompassing the best coins from this parent population in terms of both rarity and condition.

Perhaps because they were the Fairmont coins currently being sold in August, 2020, when I first became aware of the Fairmont Collection, or perhaps because I have an affinity for the series, I have focused considerable attention on the Fairmont half eagles and, in particular, on those minted between 1834 and 1866. I will refer to these as the no-motto half eagles (NM $5s), because I include the Classic Head coins in the category, along with the no-motto Liberty Heads (the Classic Head coins, of course, also do not bear the motto: “In God We Trust”).

I decided to compile a database for the Fairmont NM $5s. By searching SBG’s auction records, PCGS certification and population report data, plus several dealer inventories, I have built a database for the Fairmont NM $5s that I believe to be more-or-less complete.

This has been possible because the Fairmont coins have been almost always submitted to PCGS for certification and grading in large batches, sometimes numbering hundreds, or even thousands, of coins. Some of these batches have been date sets, but most of them comprise only a few date/mint varieties, and frequently only one. The coins in each batch end up with sequential (or, at least, nearly sequential) PCGS Certification Numbers (“Certs”). Accordingly, when one Fairmont coin has been identified (from an SBG sales catalog, for example), it is often easy to find many more, simply by inspecting the nearby coins the PCGS Cert Verification database.

This simple strategy, however, has limitations. It is not possible to search the PCGS Cert Verification database for a specific issue (1861 half eagles, for example) or pedigree (Fairmont Collection, for example) - it can only be searched by Cert Number. This is extremely inefficient and time-consuming; PCGS has assigned some 13 million Certs during the past six years (i.e., during the Fairmont era), and it is obviously impossible to inspect them all. Accordingly, a sampling procedure must be used, and this entails a likelihood that coins of interest will be missed, even in cases when it is possible to narrow the search.

Furthermore, the sheer number of coins in the Fairmont parent population renders the direct search technique impractical. Instead, I have developed a method for estimating numbers for Fairmont coins by analyzing time series, which I have constructed from historical records of the PCGS Population Report (Pop Report) database. These time series track the cumulative counts of US gold coins graded by PCGS for every date/mint variety, starting in late 2017 and ending at the current time, with a two-month cadence. When a batch containing a significant number of coins for a single date/mint variety is graded (e.g., a batch of Fairmont coins), an upward jump appears in the corresponding time series that is easy to spot.

According to the PCGS taxonomy, there are 121 varieties of NM $5 half eagles, including the “zombie” 1853-D (Medium D) variety that is no longer recognized by PCGS in its Coin Facts, but does appear in the PCGS Population Reports as ten coins. Doug believes this variety does not actually exist. My NM $5 database enumerates 3,419 Fairmont half eagles, distributed among these 121 varieties, ranging from six varieties with no coins to the 1861-P, with 750. In addition, there is a single 1849 Territorial half eagle among the Fairmont coins.

I have constructed time series for all these varieties.

The goal of this article is to validate a procedure for estimating the number of Fairmont coins directly from the time series, using my database for the Fairmont NM half eagles as “ground truth.” Once validated, this procedure will then be available to analyze other groups of Fairmont coins (the Carson City $20s, for example), for which I do not have a complete database.

In subsequent articles, I plan to extend this study of the Fairmont NM half eagles in three additional directions: (1) Apply the attrition model that I developed in my introductory chapter for the fourth edition of Doug’s Dahlonega book to the Fairmont NM $5s; (2) Extend the survival analysis that I described for the Fairmont Dahlonega half eagles in my previous blog piece to (at least) the Fairmont NM $5s from New Orleans and Charlotte; and (3) Undertake a study of the condition of the Fairmont NM $5s relative to the universe of all NM $5s that PCGS has graded, now that it appears that the series of Fairmont sales is finally nearing its end.

With these four procedures in the toolbox, it should be possible to perform a meaningful analysis of all the denominations and varieties of the Fairmont coins.

Reprise: Another Dose of Time Series Analysis

The reader may recall that I devoted considerable space in the second article in this series to a discussion of time series. However, rather than simply refer the reader to that article, I will recapitulate the important parts of that discussion here, and then elaborate on the analysis procedure itself.

The figure below is the time series for the 1861 half eagles, shown as a simple bar chart with dates attached - 21-01, for example, is January, 2021. A previous version of this chart appeared in the earlier article.

The most prominent feature of this time series is an upward jump of 725 coins graded in January, 2021. In May, 2022, another jump in the PCGS Pop Report number for the 1861 $5s occurred, but this one was downward - the total was reduced by 193 coins. It is not unusual to find reductions of a few coins in the various time series, which probably indicate cross-over coins or re-grades, but a downward jump of 193 coins is remarkable. I eventually realized that the large downward jump in the 1861 $5 time series is not a one-off, but has happened for several other issues as well, so it invited further investigation.

1861 $5.00 PCGS MS62 CAC, ex SBG/Fairmont

The jumps occur against a variable, but generally slowly rising, background - this background is simply the stream of 1861 half eagles that pass through PCGS grading all the time, and most of them are, undoubtedly, not Fairmont coins. Thus, this time series presents one of the most common problems in time series analysis - the extraction of a signal (in this case, the jumps) from a variable (i.e., noisy) background. Of course, this background is always present, and it is present during the jumps, also. One cannot simply conclude, therefore, that the 725 coins from the January, 2021, jump were all Fairmonts - some of them were from the non-Fairmont background, and that number must be estimated and removed.

In early 2022 I decided to track down the PCGS Certs for the 725 coins for the January, 2021, jump, because I had set the goal of finding the Certs for all the Fairmont NM $5s. I found Certs for 695 1861 $5s, graded as seven single-date batches of about 100 coins each. The numerical gaps between the seven sequences are short, so there can be little doubt that the coins were all graded at about the same time, and the specific Cert numbers point to early 2021 - they are undoubtedly the “jump” coins.

Embedded within the seven sequences were 26 numbers that returned the PCGS Invalid Cert message - whether these numbers had ever corresponded to actual coins is, of course, unclear. Experience has shown that there are occasionally gaps in PCGS Cert number sequences, even for newly-graded PCGS coins, and perhaps these missing numbers correspond to Certs that were spoiled in some way during the grading process, or to some other clerical feature of PCGS’s Cert management system. Or, perhaps the 26 missing Certs corresponded to coins that had been removed from the PCGS database at some point between early 2021 (when the coins were graded) and early 2022 (when I made my list), as cross-overs or re-grades.

Assuming the 26 invalid Certs corresponded to actual coins at one time, the implied total was 695 + 26 = 721. The remaining four coins (725 - 721) were presumably non-Fairmonts (i.e., background coins) that just happened to be graded at the same time as the Fairmonts.

In November, 2023, in the course of investigating the downward jump of May, 2022, I decided to re-examine my list of the Fairmont 1861 $5s, and discovered that it now contained 214 additional Invalid Cert entries, along with the 26 I had noted in early 2022. Unlike the 26 examples from 2022, however, there can be no doubt that the additional 214 missing entries had all been, at one time, assigned to actual coins - I have a list of those coins, after all. However, between early 2022 and November, 2023, they became “ghost” coins - coins that no longer exist as valid PCGS-graded coins. There is little doubt in my mind that the reduction of 193 coins that PCGS reported in May, 2022, accounts for most of these 214 ghost coins - there is, really, no other possibility. Evidently, Fairmonts can become ghost coins, and it may happen rather often.

Precisely what happened to these ghost Fairmonts is not clear. Perhaps they were sent elsewhere (to NGC, most likely) as crack-outs or cross-overs. There is no evidence in the PCGS time series that they remained with PCGS - for example, the time series has never fully recovered from the downward jump - so they probably were not simply re-grades that received new Cert numbers. In any case, PCGS evidently knows that something happened to these ghost coins, because they adjusted the Pop Report numbers.

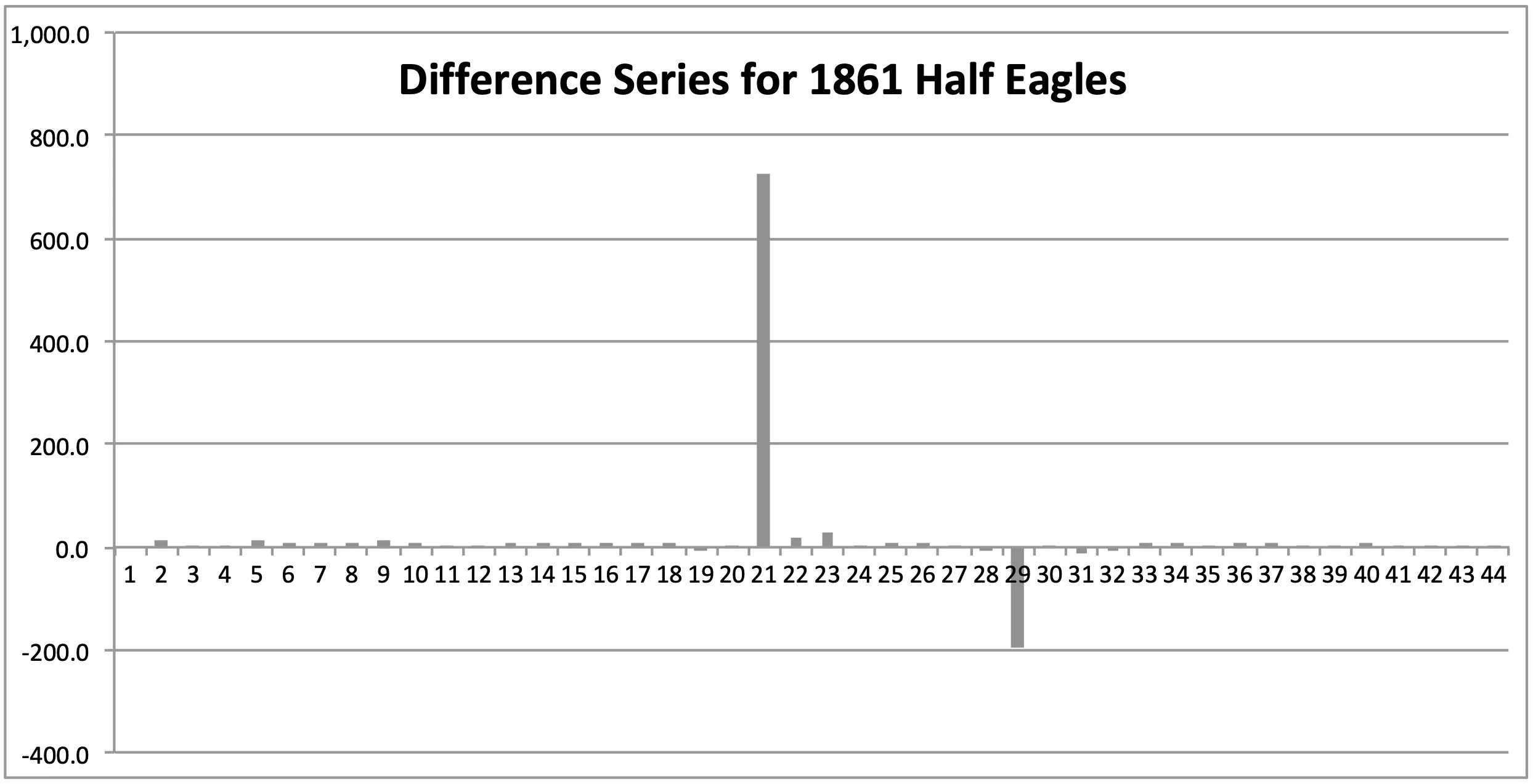

The numerical procedure I developed employs a common trick used in time series analysis - rather that investigate the time series itself, I analyze a “difference series” for which each number in the original time series is subtracted from its successor. In this derivative series, the jumps become prominent spikes (the “signal” - both upward and downward, in this case), and the background becomes a much shorter “lawn” of more-or-less constant height (the “noise”). The difference series for the 1861 half eagles is shown below.

The goal is to accurately determine the height of the background “lawn,” ignoring the larger spikes. A simple average doesn’t work, because it is strongly biased by the spikes. A median is better, but it is still biased by the spikes.

Eventually, I settled on the “TRIMMEAN” function in Excel. This function returns the mean (or average) of the interior of an ordered data set (i.e., re-arranged in numerical order, from small to large). TRIMMEAN calculates the mean taken by excluding a percentage of data points from the top and bottom tails of the ordered data set, thereby excluding outlying data from the analysis. After some numerical experimentation, I decided to exclude the lower and the upper quarters of the ordered data, thereby using only the middle half for the calculation.

By subtracting the TRIMMEAN result from each element of the difference series, I removed the (non-Fairmont) background.

The next problem was to deal with the ghosts - i.e., Fairmont coins that no longer have valid PCGS Certs. The key to success was the fact that ghosts also seem to occur as batches, so they appear as large downward spikes in the difference series. In contrast, small negative numbers in the “lawn” probably indicate cross-overs or re-grades, and are a valid component of the background.

After some further numerical experimentation, I decided that a downward spike in the original difference series (i.e., uncorrected for the background) that exceeds -5 probably corresponds to a batch of ghost Fairmonts.

The final step in the estimation process is to sum the elements of the background-corrected difference series, excluding the ghosts. In this manner, I arrive an estimate of 759 for the total number of Fairmont 1861 half eagles, with a likely error of perhaps ±10-20 coins.

The TRIMMEAN result derived from the 1861 $5 series was 5.43 coins, which represents the average number of non-Fairmont 1861 half eagles graded every two months by PCGS over the seven years from late 2017 to late 2024. The total is 234 coins. The ratio of these non-Fairmont “background” coins to the Fairmont coins is 234 / 759 = 31%, a percentage that probably characterizes all the different varieties. Obviously, neglecting to correct the estimates for this background would be a fairly serious error.

From my database of Fairmont NM half eagles, I believe that the actual number of Fairmont 1861 half eagles is 750, 749 with PCGS numerical grades, and one with a PCGS-Details grade. Because the PCGS Pop Reports, which underlie my time series, exclude impaired coins with PCGS-Details grades, the relevant comparison is 749 (actual) vs 759 (estimate).

Impaired Coins

Among the 3,419 Fairmont NM half eagles that I have enumerated in my census, 275 - almost exactly 8% - are impaired, with PCGS-Details grades. Thus, finding only one impaired coin among 750 Fairmont 1861 $5s seems to be, in fact, rather unusual - one might have expected about 60. Perhaps the coins exist, and I simply never found them, however unlikely this may seem.

The time series are based on PCGS Pop Report numbers that do not include impaired coins, so impaired coins are invisible to the time series analysis described above. In fact, other than in its Cert Verification database, PCGS seems largely to ignore impaired coins.

And so, it turns out, does Stack’s Bowers, at least for Fairmont coins. Although SBG included impaired coins in some of its earlier Fairmont sales, there have been none in its Fairmont auctions for the past year or so, and not even in its Collectors Choice sales, which often include non-Fairmont impaired coins. In fact, I know of several impaired Fairmonts that have lost their pedigree - when originally graded, they carried the “Fairmont Collection” pedigree on their holders, but now they do not. Evidently, these impaired coins were returned by the Fairmont manager (presumably SBG) to PCGS for re-holdering without the pedigree.

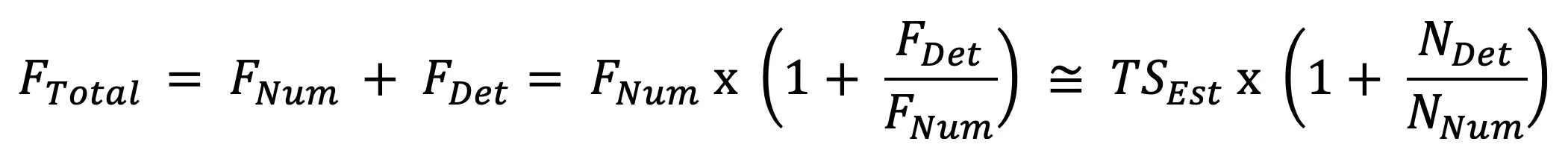

Fortunately, NGC does publish a census of impaired coins, which can be used to estimate the number of impaired Fairmont coins, without explicit appeal to an actual enumeration. Algebraically, the procedure may be expressed as:

where F denotes a Fairmont number, N denotes an NGC number, TS denotes a number derived from a time series, and the subscripts “Num,” “Det,” and “Est” designate numerical grade, details grade, and estimate, respectively.

Because the PCGS Pop Reports, which underlie my time series, exclude impaired coins with PCGS-Details grades, the time series analysis results in an estimate for FNum, not FTotal. My Fairmont database would provide directly, were its enumeration complete. It isn’t, however, except (perhaps) for the NM $5s. Instead, I will use the NGC data as a substitute (i.e., the expression on the right side of the above equation).

For the Fairmont 1861 half eagles, the result is:

Obviously, this estimate is considerably larger than the 750 obtained through direct enumeration. The difference arises from the impaired coins, which I believe the direct enumeration under-counts. The remainder of this section will discuss this point.

The NGC numbers for impaired coins are rather sobering. As of late October, 2024, almost 26% of the NM half eagles that NGC has ever graded are impaired. For the 1861 $5, the fraction of impaired coins is about 15%, a number that implies 138 impaired Fairmont 1861 half eagles, not just one!

The NGC numbers suggest that the fraction of impaired coins is larger for earlier dates, consistent with expectation. For example, the fraction of impaired coins among the NGC-graded Classic Head half eagles of 1834-1838 is almost 40%. For the Liberty Head NM $5s, the fraction drops to about 21%, and is a bit higher for the earlier dates than the later dates. The medians, which are less sensitive to outliers and, in this case, to large variations in mintage, also, show a similar pattern.

Among the Fairmont coins, the fraction of impaired Classic Head half eagles is 37%, and I have believed for some time that essentially all the Fairmont Classic Head $5s were submitted to PCGS for grading, including the impaired coins. The fact that the NGC fraction (40%) and the Fairmont fraction (37%) are comparable reinforces this belief.

For the Fairmont Liberty Head NM $5s, however, the fraction drops dramatically, to about 6.5%, and decreases to less than 1% for the half eagles issued in the 1860s. Something is clearly amiss.

Besides date-of-issue, there are a couple other obvious ways to carve up the data: by mint and by scarcity. Scarcity is, of course, somewhat subjective. For Fairmont coins, however, there happens to be a fairly solid number - 20 examples - that separates the “scarce” varieties from the more common issues. This number is related to the auctions.

Since mid-2018, there have been about 40 SBG sales that have included Fairmont coins. However, only 15 of these sales have featured reasonably complete date runs of Fairmont half eagles, 13 sales for the eagles, and 19 sales for the double eagles. The ten named-set auctions that have occurred so far are on all three lists, but the remaining sales are not the same. For example, the very first Fairmont auction in June, 2018, had only double eagles, and the August, 2020, sale had only half eagles, and was the first to include them.

What this probably means is the following: when the Fairmont managers (presumably SBG) planned the auction structure some seven years ago, they discovered that there were only enough Fairmont coins for the scarcer varieties to (more-or-less) populate 13-19 date sets. As necessary, impaired coins were used. Thus, it may be instructive to examine whether or not impaired coins are more likely to be found among the scarce issues in my database. By scarce, I mean no more than 20 known examples among the Fairmont coins.

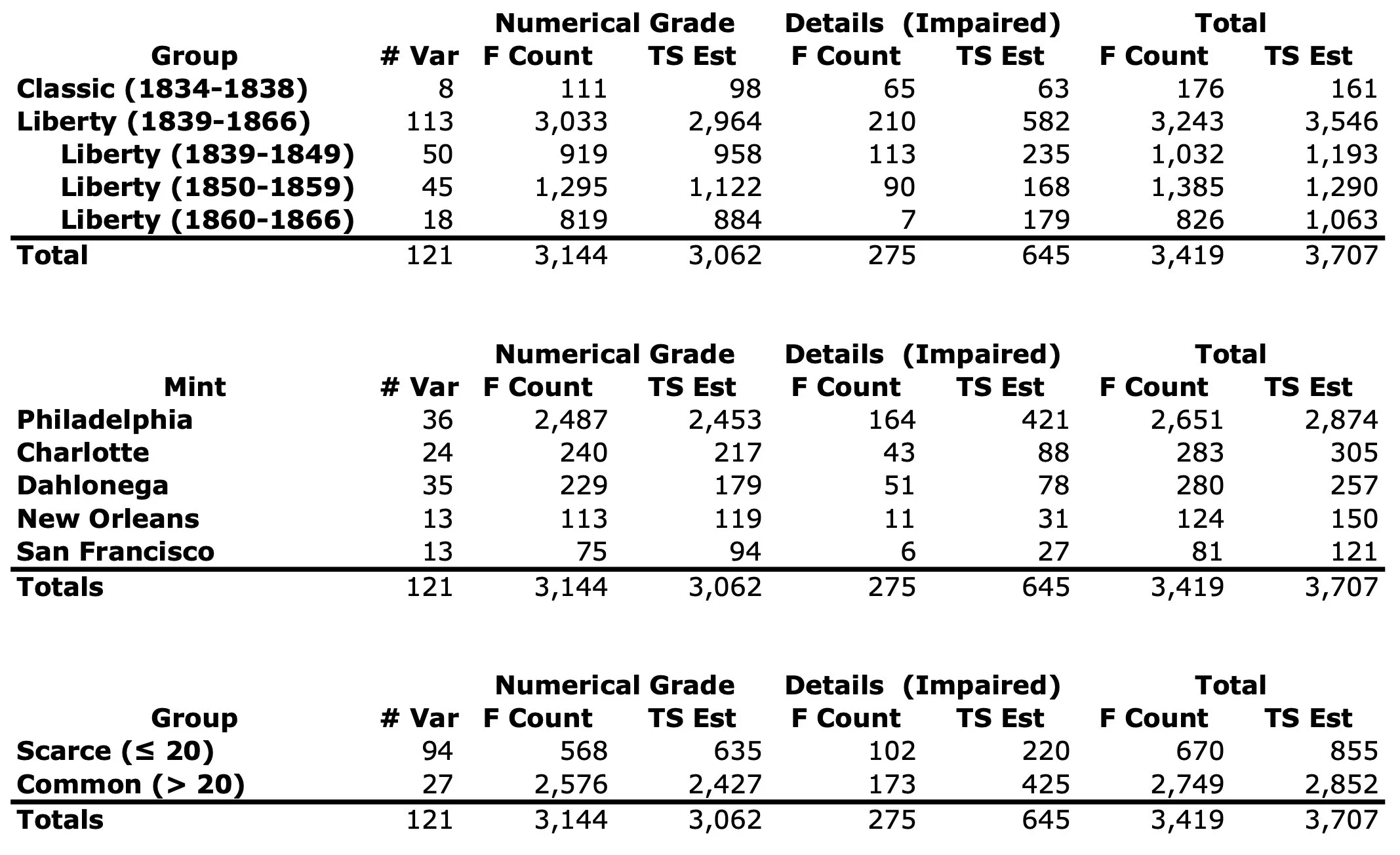

The table below summarizes all this.

Examining the table, a conclusion seems fairly clear: relative to expectations based on the NGC numbers, impaired common-date Liberty Head NM $5s (mainly Philadelphia coins), are deficient among the Fairmont NM half eagles. The 1861 $5 is one of these deficient issues.

I think the explanation for this is quite straight-forward: there exist impaired coins within the Fairmont parent population that were deemed not worth the expense of grading. I discussed these ungraded Fairmont coins in the third article of this series, and I will not repeat that discussion here.

To make the point a bit more specifically: if you are the Fairmont manager, and you have some 900 Fairmont 1861 half eagles, among which perhaps 138 are impaired (using the NGC numbers), why bother having the impaired coins graded? On the other hand, if you have only a single example of the 1834 crosslet-4, or the 1842-D (large date), or the 1842-O (which seems to be the case among the Fairmont NM half eagles), and it also happens to be impaired, you will have it graded, anyway. You will need it for your Hendricks Set sale!

Economically speaking, the difference between an impaired 1861 half eagle and a worn 1861 half eagle is not very great, so much of what I discuss above applies to both impaired common-date coins and worn common-date coins.

As the dust settles from all this, a question lingers in my mind: Do the NGC ratios fairly state the situation for the Fairmont coins?

The Classic Head half eagles suggest the answer is “Yes,” and seem to me to offer a fairly powerful argument. On the other hand, the numbers for the four branch mints, as well as those for the “scarce” varieties, suggest that the NGC ratios may overstate the situation for the Fairmont coins, perhaps by a factor of 2-3.

A certain degree of over-statement seems qualitatively plausible. The NGC numbers include everything NGC has ever graded, and some of these coins were undoubtedly pure schlock - over-dipped, cleaned, and otherwise doctored. In contrast, the Fairmont coins are comparatively pristine. In view of this, it would not be surprising if the fractional number of impaired coins among the Fairmonts were lower than the corresponding NGC numbers.

Even so, any attempt to quantify this would be simply guesswork. Accordingly, I will adopt the NGC ratios, unaltered, as my substitute for the Fairmont ratios.

A Trap for the Unwary

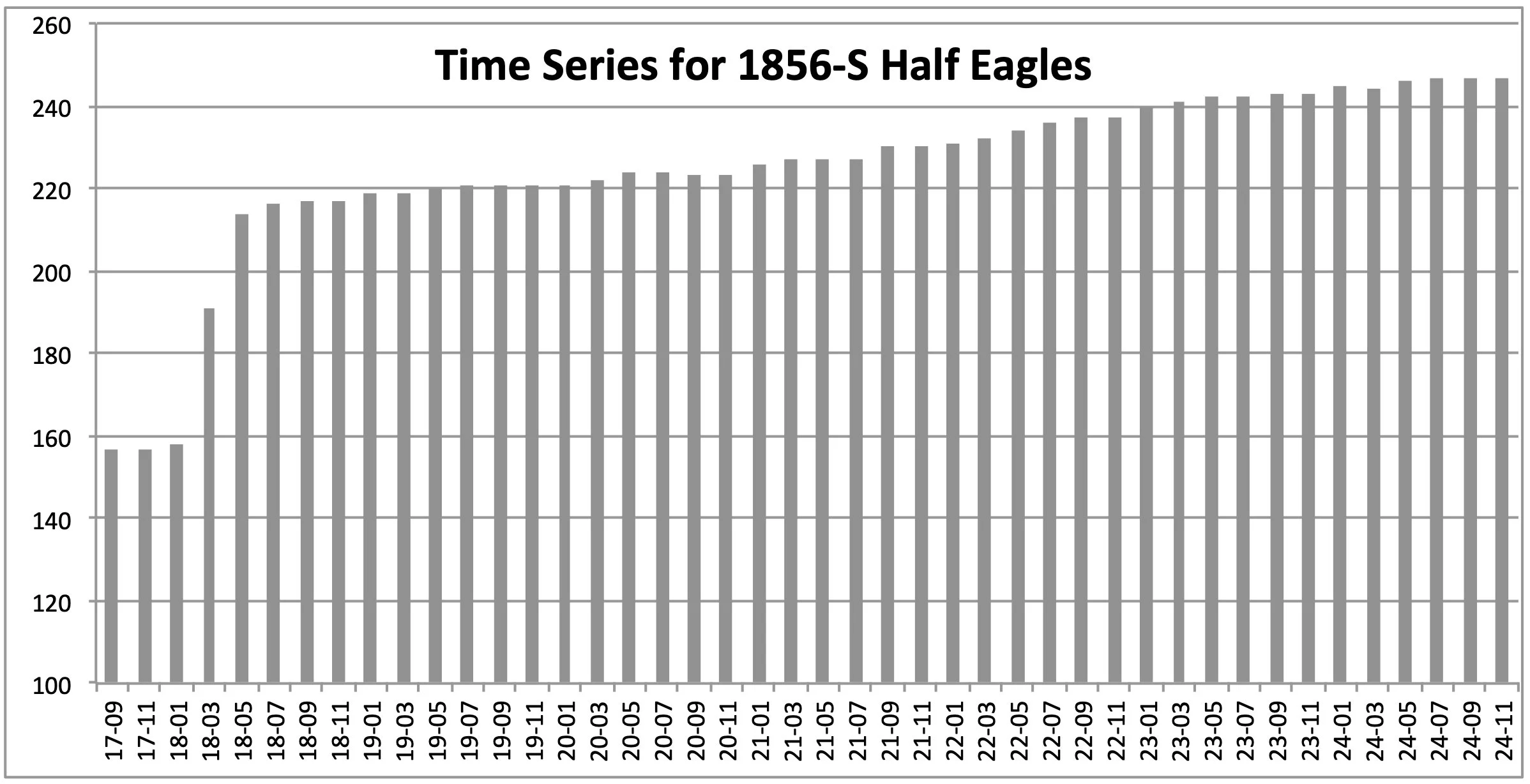

Consider the time series for the 1856-S half eagles, shown below. It looks pretty straight-forward, with two jumps in early 2018. There appear to be no “ghost” coins (downward jumps) to worry about.

The difference series is shown below. Again, very straight-forward, and the analysis procedure has no trouble delivering its estimate: 58 coins. The correction for the impaired coins is 31 coins, so the estimated total is 89 1856-S half eagles among the Fairmont coins.

However, when I consult my database, I find that there are, in fact, only 20 known 1856-S half eagles among the Fairmont coins, 17 with PCGS numerical grades, and 3 with details grades.

I did not miss 69 coins. Rather, the problem is that, although most of the jumps that occur in my time series are likely caused by Fairmont coins, some are not. In this case, the jumps are undoubtedly the signature of coins from the S.S. Central America treasure that were graded by PCGS in 2018. Similar jumps occur in 2018 for the 1855-S and 1857-S half eagles. The time series for the 1855-S, 1856-S, and 1857-S eagles and double eagles also show jumps in 2018. None of these are due to Fairmont coins.

There are probably other instances like this, of which I remain unaware.

In this case, the fix was simple: I simply excluded the 2018 portion of time series from the analysis. When this was done, the procedure delivered an estimate of eight coins. The correction for the impaired coins is four coins, so the (corrected) estimated total is 12 1856-S half eagles among the Fairmont coins.

Results and Discussion

The table below summarizes the results. The data are carved up in the same three ways as in the section on impaired coins. For each line, there are three pairs of corresponding numbers, one from my enumeration of the Fairmont NM half eagles (“F Count”), and the other from the time series analysis (“TS Est”). The three pairs present the results for the coins with numerical grades, details grades (impaired), and the total, which is simply the sum of the other two.

There is a lot to digest here, and I will allow the reader to explore the table with only a couple comments from me.

Perhaps the most satisfying result is how well the time series analysis procedure works, at least when large numbers of coins are involved (e.g., the Philadelphia and Totals lines). For large numbers, the times series estimates match the actual counts of Fairmont coins with numerical grades to within a few percent. Even for the smaller numbers, the match is not too bad - Dahlonega seems to be the outlier in this respect, which may invite a bit more investigation at some point in the future.

According to the total (actual) counts, Dahlonega and Charlotte are in almost a dead heat in terms of their numbers in the Fairmont hoard - 283 and 280 coins, respectively. Each makes up slightly more than 8% of the total number of Fairmont NM half eagles. New Orleans and San Francisco lag a bit, and this cannot be accounted for solely in terms of mintage - this will become a topic for a subsequent article.

I will conclude this rather technical article by re-stating an important point: the best I can obtain from any individual time series is an estimate for the total number of Fairmont coins have been graded by PCGS between late 2017 and the present, and not an exact count. Like any estimate, it is inherently imprecise. I believe this uncertainly to be about ±10 coins, perhaps a bit fewer for the scarcer issues, and more for the common dates (e.g., the 1861 Philadelphia half eagles), for which hundreds, or even thousands, of Fairmont coins exist.

The value of this procedure is its ability to accurately estimate the numbers for the more common issues of gold coins in the Fairmont hoard. For the scarcer issues, the actual counts will be more accurate, and my database will provide these numbers. The dividing line will probably be at about 20 known examples.

Of course, all this would be unnecessary if we had definitive numbers characterizing the Fairmont hoard. This, however, would require a decision by the Fairmont managers to release their inventory data, which they almost certainly have, but have chosen to keep private. In its absence, I will continue to work with what I have, despite its flaws.

Appendix: Data Tables for Individual Varieties of No Motto Half Eagles